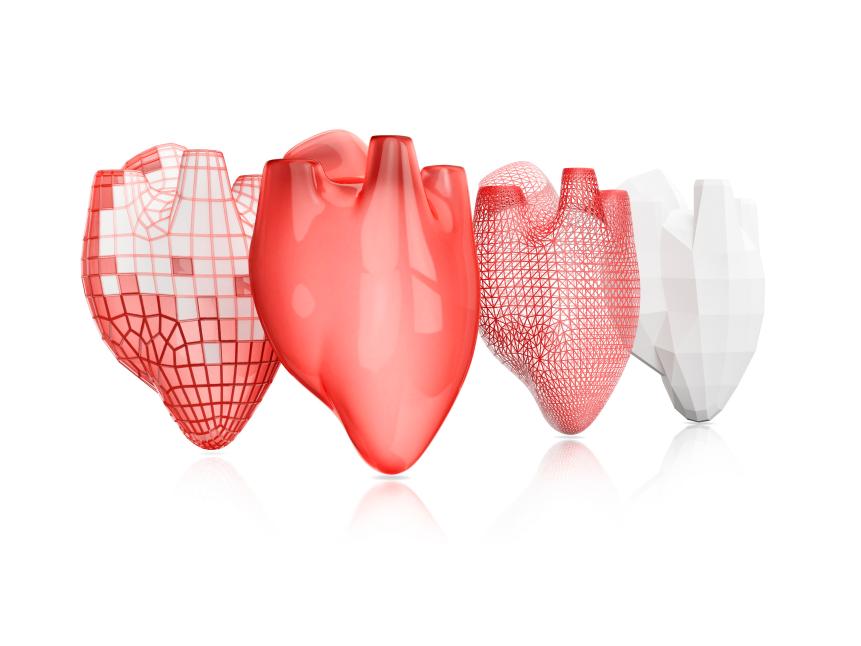

Bioprinting is the medical and biotechnology equivalent of 3D printing. By using the same principles, the aim is to rapidly develop living structures resembling human-grown organs and tissue that can be used to heal people or test new drugs.

Precision Medicine

Medical fields such as cosmetic surgery, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine operate on the principle that we can precisely manufacture tissue or whole body parts to help the body repair itself. Bioprinting offers the accuracy of precisely measured biology alongside rapid manufacture so we can heal people more quickly and effectively.

Of course, printing biological tissue is much more complex than building a mechanical part. There are intricate layers of cells in living tissue that need growth factors and surrounding structures to develop successfully. To mimic this bioprinters use bioink made from cells, biochemical nutrients and biological scaffolds to support cells in a precise order.

Additional Materials Required

Bioinks have to operate under conditions that are suitable to living, growing tissue, so they cannot really be printed at temperatures that exceed body temperature. They use a binding agent – often a biopolymer gel, or hydrogel – that acts as the molecular scaffold.

Common components of bioinks include collagen and hyaluronic acid, active molecules found in extracellular matrix (ECM) in the body, plus substances like alginate, a vegetable biopolymer refined from seaweed that retains water. Creating the right cell matrix helps the cells to stick together, communicate with each other and turn into the right types of cells to make the target tissue.

The Process is Real

Perhaps the simplest form of bioprinting is inkjet printing. Bioink is sprayed through tiny nozzles so it has to be almost liquid and this limits the biological materials that can be printed. Most 3D printers operate by extruding material through a nozzle and bioprinters can use extrusion too, though care has to be taken not to damage cells through excessive force.

Other techniques such as laser-assisted bioprinting or electrospinning – which use laser and electrical energy to position cells – are incredibly precise and can be used with thicker bioinks, but they are more tricky to use with living cells and not as rapid or able to create large quantities of tissue.

Once the bioprinter has done its work then the post-processing stage begins. Bioreactor systems are often employed to help the tissue to mature. They can be used to mimic the forces and biochemical support that tissue needs to grow and differentiate correctly.

You Have So Much Potential

Bioprinting may be a relatively new field but the results so far are encouraging. Stem cells, which have the potential to turn into several types of cells, are being used to create bone or cartilage to mend fractures and joint injuries.

Australian researchers have used neural cells in a custom-made bioink to create a ‘benchtop brain‘ that allows medics to test brain function, new drugs and study brain disorders like schizophrenia. Meanwhile, regenerative medicine scientists in the US have created a bioprinter able to construct ear, muscle and bone structures with the right size, strength and function for implantation.

One of the primary goals of bioprinting is to create functioning internal organs such as livers, kidneys or hearts. By printing compatible organs using a patient’s own stem cells, the donor waiting list could become a thing of the past. To get to this point there have been some important breakthroughs in printing vascularized tissue in complex 3D

Organ printing can improve the health of society in general by eliminating the problem of diseases caused by organ failure, costly treatments and social care. That promise may be years away from realization but rapid prototyping enabled by bioprinting is pushing medical advances forward at pace.