I was watching Netflix series- “Alexa & Katie” which is about the high school journey two best friends one of whom suffers from leukemia (blood cancer). Watching it really motivated me to find out more about the life threatening disease- cancer which kills many people every year.

While surfing I came across this article about a novel research that optimizes that our body’s own immune system can fight cancer.

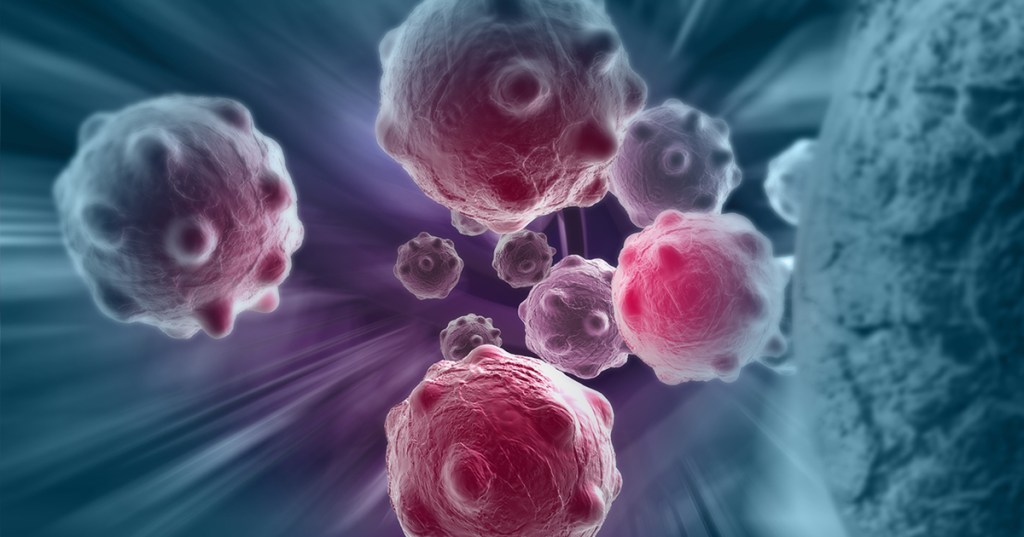

Before jumping on to the article, first, let’s look at what is cancer?

Cancer is a disease in which some of the body’s cells grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body.

Cancer can start almost anywhere in the human body, which is made up of trillions of cells. Normally, human cells grow and multiply (through a process called cell division) to form new cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old or become damaged, they die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes this orderly process breaks down, and abnormal or damaged cells grow and multiply when they shouldn’t. These cells may form tumors, which are lumps of tissue. Tumors can be cancerous.

Cancerous tumors spread into, or invade, nearby tissues and can travel to distant places in the body to form new tumors (a process called metastasis). Cancerous tumors may also be called malignant tumors. Many cancers form solid tumors, but cancers of the blood, such as leukemias, generally do not.

Armed with the basics of cancer let’s move on to the research article,

A groundbreaking study led by engineering and medical researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how engineered immune cells used in new cancer therapies can overcome physical barriers to allow a patient’s own immune system to fight tumors. The research could improve cancer therapies in the future for millions of people worldwide.

The research is published in Nature Communications, a peer-reviewed, open access, scientific journal published by Nature Research.

Instead of using chemicals or radiation, immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that helps the patient’s immune system fight cancer. T cells are a type of white blood cell that are of key importance to the immune system. Cytotoxic T cells are like soldiers who search out and destroy the targeted invader cells.

While there has been success in using immunotherapy for some types of cancer in the blood or blood-producing organs, a T cell’s job is much more difficult in solid tumors.

“The tumor is sort of like an obstacle course, and the T cell has to run the gauntlet to reach the cancer cells,” said Paolo Provenzano, the senior author of the study and a biomedical engineering associate professor in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering. “These T cells get into tumors, but they just can’t move around well, and they can’t go where they need to go before they run out of gas and are exhausted.”

In this first-of-its-kind study, the researchers are working to engineer the T cells and develop engineering design criteria to mechanically optimize the cells or make them more “fit” to overcome the barriers. If these immune cells can recognize and get to the cancer cells, then they can destroy the tumor.

In a fibrous mass of a tumor, the stiffness of the tumor causes immune cells to slow down about two-fold — almost like they are running in quicksand.

“This study is our first publication where we have identified some structural and signaling elements where we can tune these T cells to make them more effective cancer fighters,” said Provenzano, a researcher in the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center. “Every ‘obstacle course’ within a tumor is slightly different, but there are some similarities. After engineering these immune cells, we found that they moved through the tumor almost twice as fast no matter what obstacles were in their way.”

To engineer cytotoxic T cells, the authors used advanced gene editing technologies (also called genome editing) to change the DNA of the T cells so they are better able to overcome the tumor’s barriers. The ultimate goal is to slow down the cancer cells and speed up the engineered immune cells. The researchers are working to create cells that are good at overcoming different kinds of barriers. When these cells are mixed together, the goal is for groups of immune cells to overcome all the different types of barriers to reach the cancer cells.

Provenzano said the next steps are to continue studying the mechanical properties of the cells to better understand how the immune cells and cancer cells interact. The researchers are currently studying engineered immune cells in rodents and in the future are planning clinical trials in humans.

While initial research has been focused on pancreatic cancer, Provenzano said the techniques they are developing could be used on many types of cancers.

“Using a cell engineering approach to fight cancer is a relatively new field,” Provenzano said. “It allows for a very personalized approach with applications for a wide array of cancers. We feel we are expanding a new line of research to look at how our own bodies can fight cancer. This could have a big impact in the future.”

Honestly, let’s hope that this approach of treating cancer is able to save lives of millions of people affected with cancer